Be still like a mountain and flow like a great river.

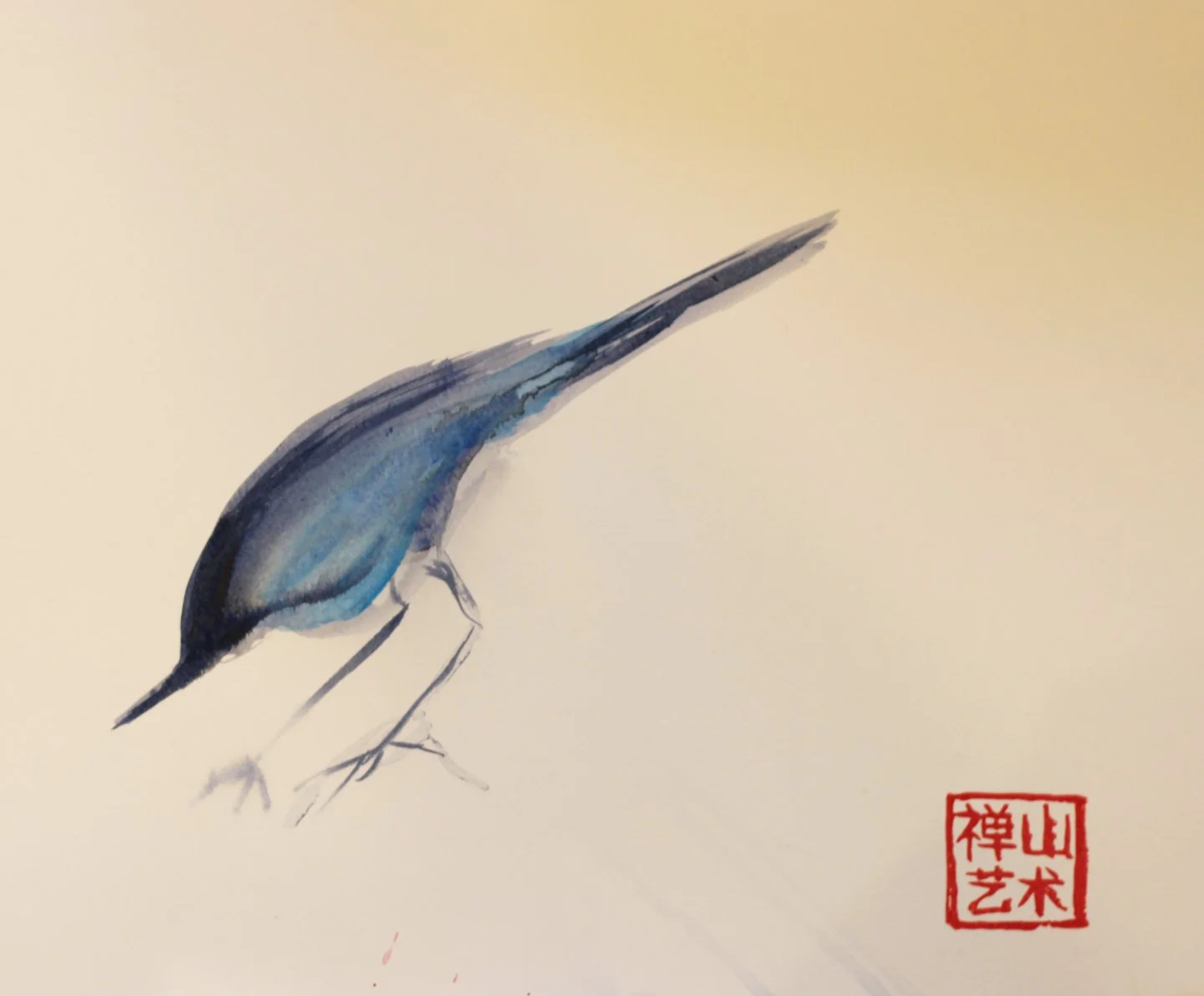

Songbird Hunting

Available original

Why do I love the mountains?

Because here, all things follow their own way.

The wildflowers bloom—no hand plants them.

The white clouds drift—no one drives them.

A wooden dipper lies ready at the spring.

A rough stone vessel holds my rice.

What need for worry? What need for schemes?

In the mountains, I am free.

- Shih-te (Pickup) - Han-shan's Companion. Shih-te (often translated as Pickup) is one of the semi-legendary Chinese Chan (Zen) figures associated with Han-shan (Cold Mountain). Together with Han-shan and Fenggan, he is part of the trio of eccentric hermit-poets who lived during the Tang Dynasty (7th–9th centuries CE) near the Tiantai Mountains in Zhejiang province.

Emptiness, stillness, tranquillity, tastelessness, Silence, non-action: this is the level of heaven and earth. So from the sage's emptiness, stillness arises: From stillness, action.

- From Zhuangzi (Chuang Tzu, 4th century BCE)

The foolish man seeks a distant paradise.

The wise man finds it under his feet.

- Ikkyū.

That’s a poem for me to think about as I think through moving from Hilton Head.

Sitting quietly,

doing nothing,

spring comes

and the grass grows by itself.

- Matsuo Bashō (17th c. haiku)

Attain the ultimate emptiness; hold fast to stillness. The myriad things stir, and I watch their return.

- Lao Tzu, Chapter 16, The Tao te Ching

From its stillness the brilliance of the world arrives

And the innumerable universes are born.

Space's vast emptiness brims over with its presence.

Yet, nowhere does it stop to take shape or form.

- Early poem from an unknown Vietnamese monk. The translation was by two ex-soldiers who fought in the Vietnam war, A U.S. veteran Kevin Bowen and Nguyen Ba Chung, a South Vietnamese veteran. Their best known work is the translation of poems by a soldier who fought against them for the North Vietnamese army (Thanh Thảo). An example: From the Lion's Mouth: Poems by Thanh Thảo.

Just Done

A month alone behind closed doors

forgotten books, remembered, clear again.

Poems come, like water to the pool

Welling,

up and out,

from perfect silence.

- Yuan Mei (18th century). Yuan Mei (袁枚, 1716–1797) was one of the most colorful and influential literary figures of 18th-century China. He lived during the Qing Dynasty and became famous not only as a poet but also as a painter, essayist, teacher, and gastronome.

. . .

Stillness, Flow, and the Resourcefulness of Being

In the old Taoist texts, life was never pictured as a battle of wills, nor as the triumph of the strongest. It was a matter of finding one’s place within the current of things. Lao Tzu counseled: “Be still like a mountain and flow like a great river.” To stand rooted and unmoving, yet to move with ease when the world requires it—this was wisdom. The sage does not rush, does not strive, yet nothing is left undone.

Zhuangzi, his inheritor in the Way, compared the mind to a mirror: “It grasps nothing, it refuses nothing. It receives but does not keep.” In this reflection lies life. The mind that clings, that anxiously tries to hold everything, becomes heavy and clouded. But the mind that receives and lets go, like still water, remains clear. “Men do not mirror themselves in running water,” he wrote, “they mirror themselves in still water.”

Centuries later, Bashō, the Zen pilgrim, found the same truth on a spring hillside: “Sitting quietly, doing nothing, spring comes, and the grass grows by itself.” To force nothing, to let life return on its own terms—this was not passivity but resourcefulness of the deepest kind. Renewal does not come through restless striving but through the patience to be present, the courage to trust the unfolding.

Han Shan, the hermit of Cold Mountain, wrote of a life lived outside the urgency of the world. “Men ask the way to Cold Mountain. Cold Mountain: there is no through trail.” The path, he implied, is not found on maps or in frantic searching. It is found when one’s heart grows quiet enough to recognize it. And when he lay under the sky, with thin grass for a mattress and blue heaven for a quilt, he embodied life not as conquest but as acceptance: enough food to eat, enough space to wander, enough stillness to know the self.

Ryōkan, a wandering Zen monk centuries later, captured the same spirit in his gentle humor: “Too lazy to be ambitious, I let the world take care of itself.” With ten days’ rice in a sack and a bundle of twigs for the fire, he had all he needed. Why fret about enlightenment or delusion, he asked, when one can simply listen to the rain on the roof?

In all of these voices, separated by time but united in vision, a truth emerges: the most resourceful act is often the refusal to grasp at foundations outside oneself. The anxious person searches for anchors in the shifting world. The sage, the monk, the poet—they rest in the foundation already within. To be still, to breathe, to let life grow as the grass grows—this is the deepest way of life.

Liquidation Sale. The Heron Dance Art Gallery in Hilton Head is closing October 31.

Later this week, hopefully Tuesday, the Heron Dance website will offer all unframed originals for $125, and all framed prints and originals for $350, including shipping. (Shipping on recent sales of unframed art has been running around $25, and framed around $250). Or, if practical, you can stop by our gallery and get any available original for $100, framed or unframed. Unframed prints at the gallery are $50 each, and $70 (if we have it in stock).

If, in the meantime, there is anything you’d like from the Heron Dance website, just email us and we’ll send a payment link reflecting the steeply discounted prices.

The only art that is excluded from this liquidation sale are a few “Zen Brush Drawings” which will be featured in an upcoming book.